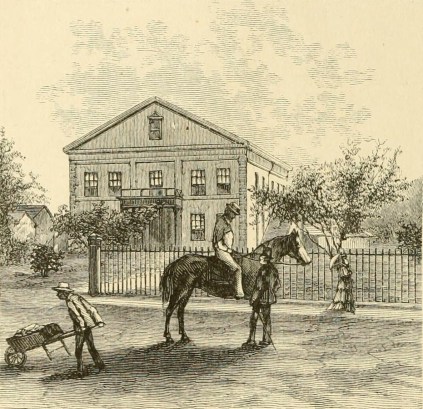

King David Kalakaua and his party visiting the US, 1874. (L-R) Gov. John Dominis of Oahu, Luther Severance (son of former US Minister), Kalakaua, US Minister Henry Peirce, Gov. John Kapena of Maui.

This is the third installment of a series about King David Kalakaua of Hawaii.

Under Lunalilo’s reign, attempts to negotiate a reciprocity treaty with the US failed amidst disagreement over the details. Hawaiian sugar planters pushed for a deal that would allow their production to arrive in the U.S. duty-free, but segments of the population, especially native Hawaiians, fiercely opposed a proposal to cede Pearl River Lagoon in order to, so to speak, sweeten the deal. With the blasting of coral reef that blocked the lagoon’s entrance, it could become a major harbor serving strategic purposes for the U.S. across the North Pacific.

When David Kalakaua was elected king in February 1874, Hawaii’s business interests made no immediate move to push again for reciprocity. They took the line that they would develop alternative markets among Britain’s Pacific colonies. But shipments to those markets actually declined, and the sugar industry remained in a slump. Within a few months, the planters petitioned the king to start new talks with the U.S.

According to one source, Kalakaua had in fact already made a secret deal with the planters during his election campaign, even promising to cede Pearl Harbor.* If this is true, it would explain why American business interests came around so strongly in favor of Kalakaua despite the perception up till then that he was anti-American. On the other hand, when it came time for the king’s envoys to visit the U.S., they were given firm instructions not to consider any cession of Pearl Harbor.** And indeed, the harbor never became an item for discussion in the 1874-75 talks. Perhaps Kalakaua skillfully manipulated the planters during the election period—but in the end the planters would get everything they wanted, and the kingdom of Hawaii would be destroyed.

The king visits the U.S.

Kalakaua needed no urging to visit the U.S. He’d talked about making a tour even before the subject of the treaty came up. As we’ll see on his 1881 around-the-world trip, he relished the idea of paying calls on heads of state, attending ceremonial banquets, and taking in the sights of capital cities. Critics would say his trips were pleasure-seeking junkets, but he did address international issues with other heads of state, and his trip to the U.S. served a definite purpose.

In August 1874 the Cabinet formally recommended a trip to Washington. Chief Justice Elisha Allen and Henry A. P. Carter, a prominent figure in the sugar business, were chosen as negotiators; the king was to follow a month later—not to negotiate but to make speeches and promote awareness of Hawaii. Allen and Carter arrived in Washington mid-November and began talks with the Secretary of State, Hamilton Fish.

In the meantime the king sailed aboard the U.S.S. Benecia to San Francisco. He and his party (see photo at top) were received with ceremonial gun salutes and greeted by military and civic dignitaries. He stayed in San Francisco for a week before journeying by rail to Washington, then progressing onward to New York, New Bedford (tied to Hawaii by the whaling trade), Boston (tied by missionaries), Niagara, Chicago, St. Louis, and back to San Francisco for return to Honolulu. Altogether his trip lasted three months.

It was a tour that would have taxed the stamina of the sturdiest constitution. As it turned out, both the king and the other native Hawaiian member of his party, Governor John Kapena of Maui, came down with severe colds early in the trip. The “Hawaiian Gazette” reported: “It is to be regretted that His Majesty allowed himself to be persuaded by the city authorities at Omaha to accept an invitation to ride out in an open carriage and view the place, in midwinter and during a snowstorm.”*** I picture the members of the royal party, accustomed to Hawaii’s balmy climate, shivering under their fur rugs. But every town wanted to give them proper hospitality, as this was the first time a foreign monarch had visited the American republic.

Once in Washington, the king spent three days holed up in his hotel, trying to recover. He emerged December 18 for a reception at the White House, where his approach was heralded by the Marine Band’s rendition of the Hawaiian national anthem. He chatted on a sofa with President Grant before other dignitaries approached and “the conversation became general.”# The next day he was presented to a joint session of Congress, but his speech had to be read for him, as his voice remained hoarse. On the 22nd, an official state dinner with thirty guests was held at the White House, the first U.S. state dinner ever held.

Then on to New York it was, where the king’s health was once again imperiled by a sleigh ride in Central Park. But by now he’d hit his stride, and he maintained a full schedule. On Christmas Day he attended a service at a big Fifth Avenue church, posed for his picture in his full dress uniform at a prominent photo gallery, made a speech to Hawaiian businessmen residing in New York, and in the evening viewed a performance of “Macbeth” at Booth’s Theater. There he was introduced to the leading players, and many champagne corks were popped. This was to be followed by a demonstration of the “promptness of the Fire Department” in response to His Majesty’s pulling an alarm, but the firemen had to be called away for a real fire. So he returned to his hotel for several rounds of billiards before retiring for the night. Due to the demands of his schedule that day, he could not accept an invitation to speak to the crowds at P.T. Barnum’s Traveling Museum, Menagerie, Caravan & Hippodrome.

The treaty negotiations

Before the king even made it back to Honolulu, Allen and Carter reached agreement with Secretary of State Fish on terms of a treaty. It called for reciprocal admission of specified items, duty-free, into the countries, and was signed January 30, 1875.

But that was only the beginning. The convention, as it was called, had to be ratified in both houses of U.S. Congress and approved by the Kingdom of Hawaii, and signed into law. The process was not formally completed until August 15, 1876 (although the treaty is generally known as the Reciprocity Treaty of 1875).

The Senate right away added an amendment that imposed a one-sided obligation on Hawaii: it must not allow any nation other than the U.S. to have preferential access to any of its ports, and it must not admit products of other nations duty-free. With this retriction, the convention was ratified by the Senate and by King Kalakaua and President Grant in spring of 1875. But an enabling bill did not even reach the U.S. House of Representatives until January 1876, due to delays in organizing that session of Congress, and in its final form it had to go back to the Senate.

In Hawaii there was general support for the treaty among both natives and foreigners, but in the U.S. the issue was debated for months. Sugar planters in the South opposed the deal, saying it would fatally injure them. Legislators argued that reciprocity treaties were either unconstitutional in principle or that the loss of duty revenues in this particular treaty amounted to a subsidy for Hawaiian planters.

These objections were overcome by a compelling argument: the treaty would protect U.S. strategic interests in the Pacific, build up American business in Hawaii, create stronger U.S.-Hawaii ties, and build new markets for American goods. To this it was sometimes added that without U.S. reciprocity, Hawaii would be forced to look to Britain and would ultimately become part of the British commercial and political system.

On June 17, 1876, Kalakaua proclaimed the treaty, and on August 15 Grant signed it into law.

An unequal deal

On the face of it, the treaty wasn’t unfair to Hawaii, apart from the lopsided restriction on the kingdom’s relations with other nations. And it did not call for the cession of Pearl Harbor. Yet one might wonder about a treaty between two nations so unequal in size. Is a deal between a classroom bully and a small kid likely to end up well for the kid?

After 1876, politicians and business interests in the U.S. made such a fuss with objections to the treaty that by 1887, when it was up for renewal, the only way Hawaii could ensure continued duty-free exports was to grant the use of Pearl Harbor as a coaling and repair station for U.S. ships. At any rate, Americans in Hawaii had no objection to that, but Kalakaua was virtually strong-armed into accepting something unpalatable to native Hawaiians. In the same year, he was forced to accept the “Bayonet Constitution ” (more on that later).

And Pearl Harbor would become a moot point by 1895, with the overthrow of Kalakaua’s successor, his sister Queen Lili’uokalani, by American interests.

In the meantime, who in Hawaii benefited from the boost to the sugar economy? Certainly not the residents whose ancestors had ruled those islands for hundreds of years. As an observer described it in 1901:

“As soon as this scheme [the 1875 treaty] was put through Congress… this gang [the sugar planters] hurried back to the islands, to cheat the poor natives out of their land before they learned that this treaty would make it worth…. What they could not buy they managed to lease for a pittance on long terms. If a native was stubborn and held onto his land they would surround him with their plantations and squeeze him out, by making his land worthless to him, for a man of small means can do nothing toward making sugar… This is the history of a hundred men who live in Honolulu and are known as sugar kings… these fellows do not think they have done much unless they make a yearly profit of a hundred percent.”##

* Michael Dougherty, To Steal a Kingdom: Probing Hawaiian History. Waimanalo, HI: Island Style Press, 1992, p. 130.

** Ralph S. Kuykendall, The Hawaiian Kingdom. Vol. III. 1874-1893: The Kalakaua Dynasty. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, 1967, p. 22.

*** “Hawaiian Gazette,” January 6, 1875, p. 2.

# “Hawaiian Gazette,” January 20, 1875, p. 2.

## Robert Meredith, Around the World on Sixty Dollars. Chicago: Thomas & Thomas, 1901. Quoted in Michael Dougherty, To Steal a Kingdom, p. 132.