Wilfred Owen. Born March 18, 1893. Died November 4, 1918.

This is one of a series about memoirs, novels, and poems authored by combatants of the First World War.

This is a short selection of poems by Wilfred Owen, who served as second lieutenant in the 2nd Manchesters. After suffering a severe concussion, he was diagnosed with shell shock and spent months recovering at Craiglockhart War Hospital in Edinburgh, where he met fellow poet Siegfried Sassoon. They inspired each other in their work. He returned to France in July 1918 by his own decision—he could have stayed on home duty. He was killed exactly a week before the Armistice at the Sambre-Oise Canal. For gallantry during an attack on the Fonsomme Line October 1-2, 1918, he was posthumously awarded a Military Cross.

He is probably the best-known among British poets of the First World War. I will not make much commentary here. I will just note that he was a serious reader of the Romantic poets of the late 18th and early 19th century (Keats, Shelley, Byron, Coleridge, Blake, Wordsworth). He often preserved the type of poetic structure they used, for instance an iambic pentameter form with rhymes. He wrote in the period shortly before the modernist explosion in poetry led by writers like T.S. Eliot and Ezra Pound, so in that sense his verse seems somewhat traditional. And yet even a superficial glance at his work shows that he had the distinctive vision essential to a poet, the ability to see things in a non-literal way that paradoxically becomes more accurate, more precise, than a literal account.

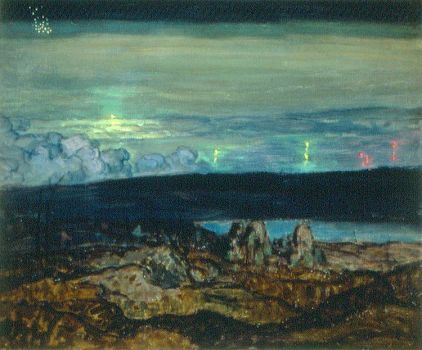

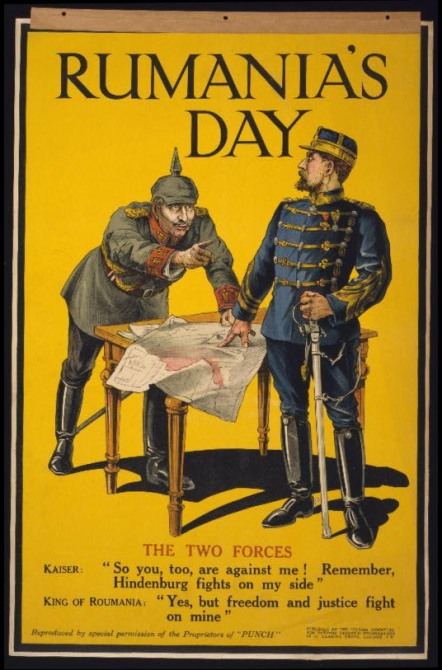

“Dressing Station,” by Ugo Matania.

This first one is a bit atypical for Owen, written in the foot soldier’s dialect. It reminds me of Kipling.

“The Chances”

I mind as ‘ow the night afore that show

Us five got talking, — we was in the know,

“Over the top to-morrer, boys, we’re for it,

First wave we are, first ruddy wave, that’s tore it.”

“Ah well,” says Jimmy, — an’ ‘e’s seen some scrappin’ —

“There ain’t no more nor five things as can ‘appen;

Ye get knocked out; else wounded — bad or cushy;

Scuppered; or nowt except yer feeling mushy.”

One of us got the knock-out, blown to chops.

T’other was hurt, like, losin’ both ‘is props.

An’ one, to use the word of ‘ypocrites,

‘Ad the misfortoon to be took by Fritz.

Now me, I wasn’t scratched, praise God Almighty

(Though next time please I’ll thank ‘im for a blighty),*

But poor young Jim, ‘e’s livin’ an’ ‘e’s not;

‘E reckoned ‘e’d five chances an’ ‘e’s ‘ad,

‘E’s wounded, killed, and pris’ner, all the lot —

The ruddy lot all rolled in one. Jim’s mad.

***

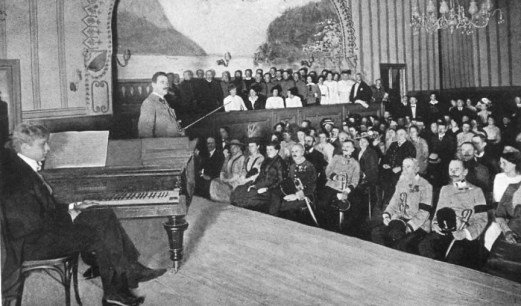

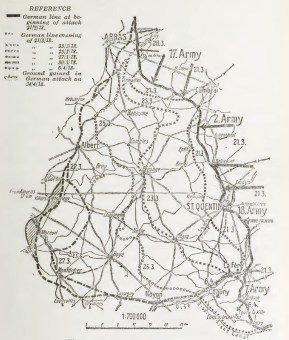

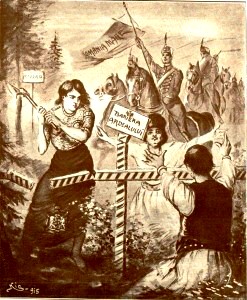

“Destruction of Arras, 1916,” by George Washington Lambert.

The next one is so intensely pathetic that I can scarcely read it without weeping. Yet it is an honest account, not a tearjerker.

“Disabled”

He sat in a wheeled chair, waiting for dark,

And shivered in his ghastly suit of grey,

Legless, sewn short at elbow. Through the park

Voices of boys rang saddening like a hymn,

Voice of play and pleasure after day.

Till gathering sleep had mothered them from him.

About this time Town used to swing so gay

When glow-lamps budded in the light-blue trees

And girls glanced lovelier as the air grew dim,

— In the old times, before he threw away his knees.

Now he will never feel again how slim

Girls’ waists are, or how warm their subtle hands,

All of them touch him like some queer disease.

There was an artist silly for his face,

For it was younger than his youth, last year.

Now he is old; his back will never brace;

He’s lost his colour very far from here.

Poured it down shell-holes till the veins ran dry,

And half his lifetime lapsed in the hot race,

And leap of purple spurted from his thigh.

One time he liked a bloodsmear down his leg,

After the matches carried shoulder-high.

It was after football, when he’d drunk a peg,

He thought he’d better join. He wonders why

Someone had said he’d look a god in kilts.

That’s why; and maybe, too, to please his Meg,

Aye, that was it, to please the giddy jilts,

He asked to join. He didn’t have to beg;

Smiling they wrote his lie; aged nineteen years.

Germans he scarcely thought of; and no fears

of Fear came yet. He thought of jewelled hilts

For daggers in plaid socks; of smart salutes;

And care of arms; and leave; and pay arrears;

Esprit de corps; and hints for young recruits.

And soon, he was drafted out with drums and cheers.

Some cheered him home, but not as crowds cheer Goal.

Only a solemn man who brought him fruits,

Thanked him; and then inquired about his soul.

Now, he will spend a few sick years in Institutes,

And do what things the rules consider wise,

And take whatever pity they may dole.

To-night he noticed how the women’s eyes

Passed from him to the strong men that were whole.

How cold and late it is! Why don’t they come

And put him into bed? Why don’t they come?

***

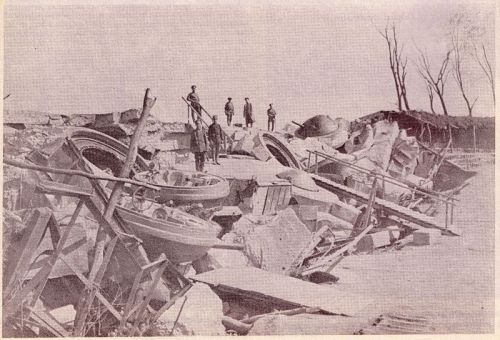

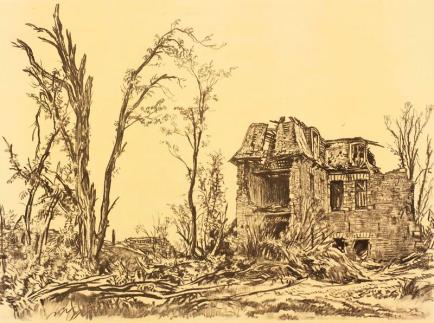

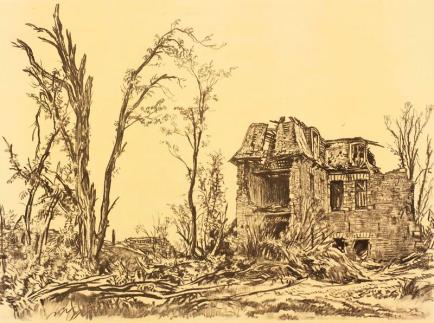

“A German headquarters,” by Muirhead Bone.

In the following, I especially like “the clays of a cold star.”

“Futility”

Move him into the sun —

Gently its touch awoke him once,

At home, whispering of fields unsown.

Always it woke him, even in France,

Until this morning and this snow.

If anything might rouse him now

The kind old sun will know.

Think how it wakes the seeds —

Woke, once, the clays of a cold star.

Are limbs so dear-achieved, are sides

Full-nerved, — still warm, — too hard to stir?

Was it for this the clay grew tall?

— O what made fatuous sunbeams toil

To break earth’s sleep at all?

***

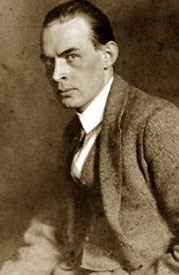

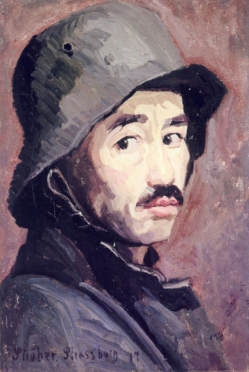

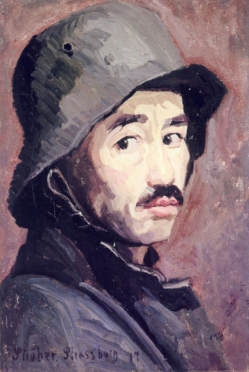

“Self-portrait with steel helmet,” by Friedrich Karl Stroeher.

The painting above is of a German soldier, not a British one, but I think the feeling depicted here is universal. It perfectly captures the vulnerability of a human being even though supposedly protected by his war gear—his steel helmet.

This next and last selection is probably Owen’s most famous poem. You can puzzle out the Latin.

“Dulce et Decorum est”

Bent double, like old beggars under sacks,

Knock-kneed, coughing like hags, we cursed through sludge,

Till on the haunting flares we turned our backs,

And towards our distant rest began to trudge.

Men marched asleep. Many had lost their boots.

But limped on, blood-shod. All went lame, all blind;

Drunk with fatigue, deaf even to the boots

Of gas-shells dropping softly behind.

Gas! GAS! Quick, boys! — An ecstasy of fumbling

Fitting the clumsy helmets just in time,

But someone still was yelling out and stumbling

And flound’ring like a man in fire or lime. —

Dim through the misty panes and thick green light,

As under a green sea, I saw him drowning.

In all my dreams before my helpless sight

He plunges at me, guttering, choking, drowning.

If in some smothering dreams, you too could pace

Behind the wagon that we flung him in,

And watch the white eyes writhing in his face,

His hanging face, like a devil’s sick of sin,

If you could hear, at every jolt, the blood

Come gargling from the froth-corrupted lungs

Bitter as the cud

of vile, incurable sores on innocent tongues, —

My friend, you would not tell with such high zest

To children ardent for some desperate glory,

The Old Lie: Dulce et decorum est

Pro patria mori.

***

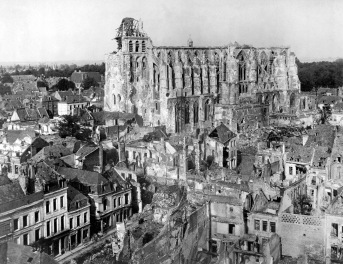

“Thiepval,” by William Orpen.

* A “blighty” was a wound serious enough to remove the injured soldier from combat but not a terrible wound, such as the kind that would require amputation of limbs. In other words, it was the ideal wound.