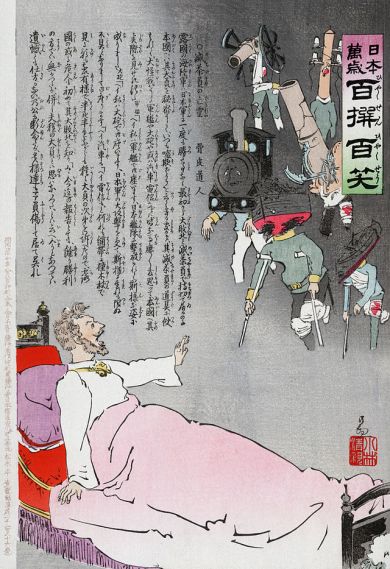

Cartoon of Tsar Nikolas awaking from nightmare of his defeated forces returning. Artist Kobayashi Kiyochika.

This is the final post of my series on the Russo-Japanese War. I have presented only topics that had a particular appeal to me, and there are many events of the war I have passed by: the battles of Liaoyang and Mukden (and others); the peace negotiations in Portsmouth, New Hampshire. The Battle of Tsushima Straits is treated in this post, but not in great detail. For further reading I recommend especially The Russo-Japanese War 1904-05 by Alexey Ivanov and Russian Battleship vs. Japanese Battleship by Robert Forczyk.

It was a voyage that literally drove some of the participants insane. The ships of the Imperial Russian Navy were never intended to serve as residences over a period of seven and a half months. Poorly ventilated, rat-infested, filled with coal dust from stockpiles heaped in every available space, each one became its own self-contained hell.

After the disastrous loss of the flagship “Petropavlosk” and the death of Admiral Makarov, Tsar Nikolas and his ministers moved to reinforce the Pacific squadron. Russia had three fleets: the Pacific, based in Port Arthur and Vladivostok; the Baltic, based in Kronstadt, near St. Petersburg; and the Black Sea, but that was bottled up because of treaty provisions that gave Turkey the right to deny passage through its straits.

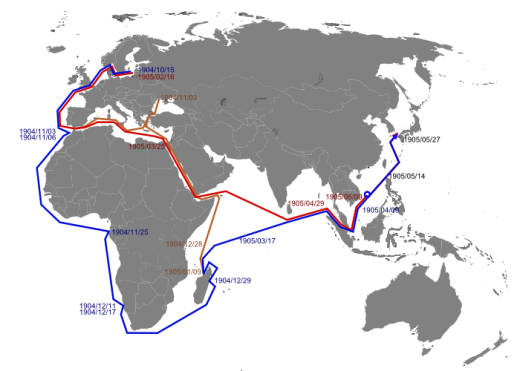

On May 2, 1904, Rear Admiral Zinovy Petrovitch Rozhestvensky was appointed to command a new squadron of the Baltic fleet, now designated the 2nd Pacific Squadron, and take it to the scene of the conflict with Japan. The better part of the squadron—including the newer battleships—would go all the way around the Cape of Good Hope, while a supplemental batch under Rear Admiral Felkerzam would pass through the Suez Canal. Some accounts state that Britain, as Japan’s ally, barred the Russians from using the canal, but this can’t be true, as subgroups of Russian warships passed through the Suez on two occasions. It appears Rozhestvensky limited his use of the canal because he saw it as hazardous. Any ships would be sitting ducks as they navigated this pinch point, and he didn’t want to risk his whole fleet. Another consideration may have been that moving the whole fleet through that narrow corridor would have created a monumental traffic jam. As it was, when Felkerzam went through, stopping to scan for enemy activity and putting his gunners on alert, a long line of merchant ships backed up behind the towering battleships, fussing and fuming.

Roshestvensky intended to sail July 15, but it was October before the fleet could be launched. It consisted of four new battleships, three older ones, seven cruisers, nine destroyers, and a bewildering array of support vessels, including a hospital ship, a repair ship, tugs, and cutters.

Apart from the elderly condition of some of the vessels, there were two other headaches for Rozhestvensky: poorly trained crews and a lack of friendly ports for resupply of coal. The four new “Borodino”-class battleships were still fitting out in the last months before the voyage, and their crews had little time to conduct training maneuvers. The experienced manpower had mostly established itself in the Black Sea fleet or already gone to the Far East with the 1st Pacific Squadron. “Thus, the crews on Rozhestvensky’s battleships consisted of too many untrained conscripts and sullen reservists, mingled in with troublemakers and agitators from other ships in the Baltic Fleet.”*

And the large 2nd Pacific Squadron needed an enormous amount of coal—about half a million tons for the whole voyage—with no ports of its own along the route for resupply. Britain of course would never assist; France imposed restrictions on the amount and timing of resupply at its ports; Kaiser Wilhelm at last offered a solution. Colliers of the Hamburg-Amerika line would meet the Russian vessels at points along the way to supply a total of 60 cargoes of coal.

The untrained crews made a mess of things right from the start. Battleship “Orel” ran aground at Kronstadt and the “Suvarov”—the flagship itself—followed suit at Liepaja in Latvia, where the squadron assembled for departure October 15. And that was not the end of it. The same day, torpedo boat “Buistry” accidentally rammed battleship “Oslyabya,” knocking a hole in herself and damaging her torpedo tubes. A few days later, the fleet damaged the Danish colliers that supplied them, through collisions and inept maneuvering.

The 30-year-old Eugene S. Politovsky, a bright and responsible man, served as the fleet’s chief engineer. He would soon be crawling about in the hold of the “Buistry” seeing to the repairs. He wrote to his wife, “I got black as the devil in the bunker. I must have new overalls. I shall buy some cloth somewhere and give it to a sailor to make.”** Throughout the whole voyage, poor Politovsky ended up dealing with repairs nearly every day, constantly moving from ship to ship, clinging to flimsy rope ladders while boarding vessels in stormy midocean seas.

Writing as they approached the narrow strait between Sweden and Denmark, Politovsky confided in his wife, “We are afraid of striking Japanese mines in these waters. Considering that not long ago Japanese officers went to Sweden and, it is said, swore to destroy our fleet, we must be on our guard.” Passing through the strait, the men were ordered to sleep in their clothes, and all guns were loaded.

Dogger Bank Incident

Every unknown vessel on the waters began to look Japanese. A few days later, in the North Sea, the fog of paranoia led the captain of repair ship “Kamchatka” to signal that he was under attack on all sides by eight torpedo boats. When nothing actually happened, he didn’t say it was a false alarm, only that he had altered course and the torpedo boats had gone.

Later that night occurred the infamous Dogger Bank Incident. The Russians fired on an innocent British fishing fleet out of Hull in the belief the trawlers were enemy torpedo boats. One trawler was sunk and its captain and first mate killed. Six other fishermen received wounds; of those one died later. Four more trawlers were heavily damaged. All at once Russia and Britain stood on the brink of war.

To the British it was both a tragedy and a farce. What insanity! The idea of Japanese warships in the North Sea! According to one British account, Russians on the “Borodino” even charged about with cutlasses shouting that the Japanese were boarding.# Over the years, the Dogger Bank episode has been heavily mined for its comic value. But, to be fair, it wasn’t completely unreasonable for the fleet’s captains to believe the Japanese could take action in the North Sea. After all, most of the Japanese war vessels were built in British shipyards and came through these waters. Russian coastal agents were paid to keep a lookout, and they misidentified vessels. Rumors flew left and right. The torpedo boats rode low in the water, hard to make out clearly—so any vague shape in the distance might seem to pose a threat.

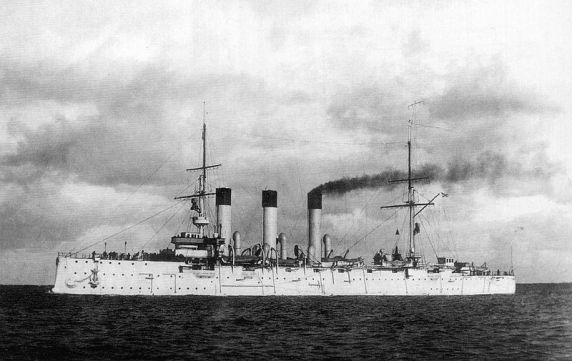

The international flap was eventually settled without the two sides going to war, but the sensitive, nervous Rozhestvensky was left with an abiding humiliation. To make matters worse, in those hours of pandemonium on the night of October 21, the Russians had even taken one of their own cruisers to be an enemy ship. Six shells struck the “Aurora,” and the ship’s chaplain had his hand torn off. It was probably no consolation that poor gunnery skills prevented further damage either to trawlers or to Russia’s own ships. The battleship “Oryl” is said to have fired over 500 shells on the occasion without hitting a thing.

The misery of the voyage

“Lying on my back last night I watched the rats making themselves at home in my cabin. I used to sleep with my feet towards the door, but have now put my pillow there…. They can jump from the writing-table on to the settee, and could easily have jumped on my head.” Thus Politovsky wrote to his wife as the fleet approached the Spanish coast. The rats would get worse as the voyage went on—much worse. Meanwhile the climate grew hot and stuffy. As they continued southward, a prankster on the flagship shaved the white curly hair off the mascot dog “Flagmansky” to prepare him for the equatorial heat, leaving his head like a lion’s. Politovsky found that drawers in the wooden tables no longer closed, and metal objects rusted. Perspiration poured off him. Towels would not dry, and coal dust filtered into the cabins.

They celebrated the crossing of the Equator with a program of actors got up as Neptune, Venus, devils, tritons, and Russian peasant women. Buglers played as the company marched through the ship, their bare chests and arms painted in all colors. Everyone from captain on down was dunked in a huge bath beside the turret—people who tried to hide were especially hunted out.

A furious gale assaulted them as they rounded the Cape. Approaching Madagascar, they learned of the surrender of Port Arthur and the sad destruction of the remaining vessels of the 1st Pacific Squadron. Once they reached Madagascar, they anchored off the island of Nossi-Be and stayed there the next two and a half months as they joined with Felkerzam’s division and awaited decisions from St. Petersburg.

Ah… the tedium. Men began to go mad. An old acquaintance of Politovsky’s wandered about the boats half-undressed, asking people if they feared Death. Eventually Rozhestvensky collected an assortment of misfits to ship back home through the Suez aboard the “Malay”—lunatics, drunkards, invalids, men imprisoned for mutinous acts. As the “Malay” departed the harbor, a group of mutineers seized control of the ship—but an armed crew went aboard and restored order. Some of the worst were simply put ashore and abandoned to fate.

The officers spent much time ashore drinking heavily and gambling for high stakes at games of vint and macao. Eventually the French governor had to order his officials not to play with the Russians, who were hijacking their time and emptying their pockets. For other amusement, men collected exotic animals and kept them aboard. “Wherever you look now you see birds, beasts, or vermin. On deck oxen are standing ready to be slaughtered for meat, to say nothing of fowls, geese, and ducks. In the cabins are monkeys, parrots, and chameleons,” Politovsky wrote. Since Madagascar has no monkeys, he must have been referring to lemurs.

As they stewed in their juices at Nossi-Be, news came of a crushing defeat at Mukden, in Manchuria. Measured in terms of the numbers involved, it had been the largest battle in history up to that point: 300,000 Russians under Kuropatkin against 200,000 Japanese under Oyama. The Russians suffered over 40,000 killed and 49,000 wounded. “A fearful catastrophe!” wrote Politovsky. “It is useless for the fleet to go on.”

But go on they did, at last departing Madagascar March 16. St. Petersburg had decided to throw yet more warships at the Japanese, creating a 3rd Pacific Squadron out of vessels Rozhestvensky had rejected as obsolete. Rear Admiral Nikolay Nebogatov was appointed to its command. He set off with his squadron through the Suez for a rendezvous with the 2nd Pacific off French Indochina (in what is now Vietnam).

In the view of Rozhestvensky, these delays only gave Admiral Togo more time to organize his fleet—and just for the sake of adding ships he categorized as “self-sinkers” and “an archeological collection of naval architecture.” Deeply annoyed, he tendered his resignation, but the Tsar rejected it.

The 2nd Pacific steamed eastward across the Indian Ocean. “There was a great show in the wardroom in the evening. A rat hunt was organized, and many were killed.” “I lay down to rest, but could not sleep owing to the heat. I sleep completely uncovered, and keep a small piece of cardboard by me and use it as a fan.” “Yesterday a sailor from the ‘Kieff’ flung himself into the sea and drowned.” Politovsky occupied himself by calculating and recalculating the number of days before they should reach Vladivostok. But they would never make it that far.

The Battle of Tsushima

On May 11 the 3rd Pacific joined them at Cam Ranh Bay. Now the enormous assemblage of vessels headed north—toward Japan. For Politovsky, reality began to sink in. He’d been fixating on the goal of Vladivostok, as if their only purpose was to shift to a different base of operations, but they were bound to engage the Japanese fleet on the way. As they approached the vicinity of Japan, he wrote to his wife, “Yesterday I began to prepare for battle. My preparations were very simple. I opened a trunk, and without more ado thrust in everything—icons, letters, and photographs of you.”

Admiral Togo had been monitoring the Russians’ progress all along. On May 25 he learned that Rozhestvensky had sent away colliers that arrived at Shanghai to meet the fleet. With no resupply of coal, he must be planning on taking the shortest route, through the Straits of Tsushima, between Japan and Korea.

Early on the morning of May 27, a lookout on the “Ural” signalled that four unidentified ships had appeared behind the column. The two fleets spent the next hours positioning themselves. Togo eventually came into position to “cross the T” of the Russians, whereby he could concentrate his ships’ fire on each of the enemy ships in turn, but the order of his battle line was such that he would have been leading with his cruisers instead of his battleships with their heavier guns. He performed a risky maneuver, ordering his entire fleet to follow flagship “Mikasa” in a big semi-circle. This put each of his ships in vulnerable position for about 15 minutes as they remained nearly stationary within gun range of the Russians.

Rozhestvensky failed to take advantage of the situation, and around 2:00 in the afternoon the Japanese opened fire. The “Suvarov” was soon dealing with a fire on board, and the “Oslybya” sank at 2:45. It was the first of quite a few Russian vessels to go to the bottom—in all, five battleships, four cruisers, and five torpedo boats were destroyed. The Japanese were to lose only three torpedo boats.

Despite its damage, “Suvarov” continued fighting through the afternoon. Rozhestvensky received several wounds, including a bone fragment in his brain. He was transferred to the destroyer “Buiyny” before his ship sank about 7:00.

It took Admiral Nebogatov quite a while even to realize that he was now in command. By the next morning his position had become hopeless, with the major Russian battleships all either sunk, scuttled, or surrendered. Several of the ships fled southward, and they would end up interned in Manila. At 10:30 a.m. Nebogatov hoisted a large white tablecloth. Some 4,800 Russians had been killed, 7,000 were captured, and 1,800 would be interned; the Japanese had 110 men killed and 590 wounded. The devastating defeat, following on the disaster at Mukden, wiped out Russia’s will to keep fighting, and in mid-June the two nations accepted an offer from the US to mediate peace talks.

After the “Suvarov” was struck that day of terrible battle, Politovsky busied himself with making repairs. He was last seen in the sick bay, conscious and inquiring as to the progress of the fight. Soon afterwards, staff members departed with Rozhestvensky for the “Buiyny.” Politovsky was left behind, and soon the ship sank.

# # #

* Robert Forczyk, Russian Battleship vs. Japanese Battleship. Oxford, UK: Osprey Publishing, 2013.

** Eugene S. Politovsky, From Libau to Tsushima. New York: E.P. Dutton, 1908. It is a collection of Politvosky’s letters to his wife, which were never intended for publication but present an honest account of the voyage, albeit rough and informal.

# See an account on the University of Hull website, http://www.hull.ac.uk/hmap/fig/gallery/3/DoggerBank/TheDoggerBankIncident.pdf. This telling of the story is very entertaining but not entirely reliable in its details.

Quite a saga. Apparently there were telegraphs all along the way, so that the Russians

could keep getting orders and the Japanese could also keep tabs. Were the Japanese

boats so much better (was the Russian fleet also built by the Brits?) Or was it just that

the Japanese were better trained to hit their targets and better commanded ?

The Japanese and the Russians were roughly equal in both the technology of their battleships generally and in the number of modern battleships present at Tsushima. The Russians had more heavy guns in that battle, but the Japanese guns had a faster rate of fire and a lot more medium-caliber guns, which were useful in the close-range fighting of Tsushima. The Russians had been building their own ships for a while at several shipyards.The big difference was in the training of the crews and the morale of both crews and officers. Rozhestvensky was an intelligent man and a gunnery expert, but he was totally demoralized—supposedly he suffered a nervous breakdown on the voyage. Togo made mistakes sometimes but overall was a superb commander.

This was an astonishing voyage by any measure – tragic and heroic in equal portions. And Tsushima was pored over afterwards by naval architects as the only example of late industrial battleship conflict, in particular the test of French (Russian) vs British (Japanese) principles. All the wrong conclusions were drawn, unfortunately – such as the notion that armoured cruisers and their dreadnought-style descendants, the battlecruiser, could stand in the battle line. Amidst all of that we must, of course, remember that ultimately Rozhestvensky’s voyage was a human story – as you’ve revealed. Love the quote about the on-board rats.

Thank you. I think one of the most interesting subtexts was Rozhestvensky’s personality, a subject I didn’t have time or effort to explore. Again, thank you for your interest.

Thank you for posting! I find history fascinating, especially the period you’re covering – something I’ve written on extensively myself. It would be wonderful if more people became interested in that era, because it tells us so much about how the twentieth century was shaped – and thence, of course, today. All good stuff.

Warfare is a fascinating subject. Despite the dubious morality of using violence to achieve personal or political aims. It remains that conflict has been used to do just that throughout recorded history.

Your article is very well done, a good read.