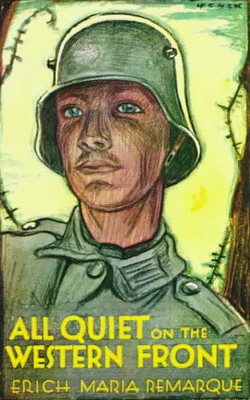

This is one of a series about memoirs, novels, and poems authored by combatants of the First World War.There are many editions of Erich Maria Remarque’s

All Quiet on the Western Front. I used an e-book edition.

This is the best known by far of any of the books I have included in these works of World War I. Yet I had not read it before I began this series. I did so at the very start but put it aside, as I did not like it very much, for the most part, though I couldn’t say exactly why. Now I have reread it, and I understand why it leaves me unsatisfied.

Of the ten works that preceded All Quiet in my “Words of endurance” series, seven were memoirs. The one other novel was The Secret Battle by A.P. Herbert, and that has such a strong autobiographical element that it reads like a memoir. The extraordinary long poem In Parenthesis also contains a lot of autobiographical material. All of these works brim over with the concrete particulars of everyday life in combat—with the random, the arbitrary, and the peculiar elements of real human experience. In fact, these writings are so embedded in the actual moment that often I found it difficult to get a sense of the historical context. A.P. Herbert doesn’t bother to tell us that the major battles of his book were the Third Battle of Krithia at Gallipoli and Beaucourt sur l’Ancre at the Somme. Hans Carossa, in A Roumanian Diary, never identifies the location of his most important experiences—through much study of maps, I determined it was the Csik Mountains of eastern Transylvania.

Not only are these works highly personal and subjective, but the authors seem uninterested in drawing out larger themes as to war’s futility or, conversely, its glory. The reader comes away with a strong sense of each author’s personality—Fritz Kreisler is patriotic, Carossa is sensitive and introspective, Ernst Juenger lives for adventure—and yet we aren’t reading these people’s opinions or interpretations.

Of those ten authors preceding Remarque in this series, only one—the poet Wilfred Owen—universalized his experience. He wasn’t interested in the random, but in the significant. His poems carried the unmistakable message that war is a futile and grotesque experience.

All Quiet was written deductively rather than inductively—going from the general to the particular. Remarque had several themes. They were: the grotesque nature of war; the importance of comradship among soldiers; the pointless nature of conflicts between nations, which after all are made up of fellow human beings; war’s disfigurement of the psyches of soldiers, especially the younger ones who go into combat wholly naive, lacking the steadying experiences of wife, children, and profession. Related to the latter, another theme is the impossibility of returning unblemished to normal civilian life.

All Quiet has to be respected for its depiction of a viewpoint unpopular in Germany after the war. But by the time of its publication in 1929, its themes resonated with many readers, and it is said to have sold 2.5 million copies in 22 languages in the first 18 months after it went to press.

Remarque’s themes were important ones. They had been addressed in various ways by the British—Owen, Sassoon, Graves, Blunden, and others—but they hadn’t been discussed to any great extent in Germany, and readers in other countries hadn’t heard much about the German experience. In the years immediately following the war, many in the Allied nations still languished under the baneful influence of anti-German propaganda. All Quiet told these readers that German soldiers were human beings like themselves.

Why, then, do I not care for this book? It has after all some lovely writing. Take, for instance, this description of a bombardment: “The dark goes mad. It heaves and raves. Darknesses blacker than the night rush on us with giant strides, over us and away.”

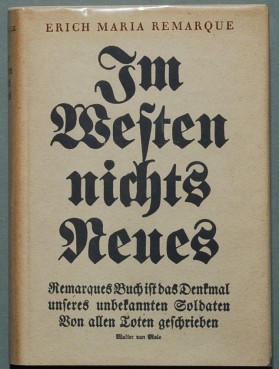

But the one thing that really stood out to me on my first reading was the artificial nature of the ending. The protagonist, Paul Baumer, is killed in October 1918—just before the end of the war. His comrades, especially the ones who as schoolmates all enlisted at the same time, have one by one been killed off or seriously wounded over the course of the book. Now Baumer dies—oh, how ironically—within a few weeks of the Armistice. Remarque has to switch awkwardly from first person to third person at the very end in order to let us know this is what happened. And, of course, at the moment our hero dies, a report goes out: “Im Westen nichts Neues”—on the Western Front nothing new—ah! the irony!

The book contains details from Remarque’s own experiences, and those are the parts that, in my thinking, carry more weight. He served on the front from June 12, 1917, to July 31 of the same year. At that time he was wounded and spent the rest of the war in an army hospital. Therefore the book’s scenes of wounded soldiers in hospitals have a special authenticity.

And no doubt many other scenes come from Remarque’s experience, and those ring true: the fixation on food, the stupidity of the dreaded Corporal Himmelstoss, the schemes to seduce French women. But, on my second reading, I perceived a certain blurred quality to much of the writing, as if the experiences were generic rather than particular. No places are mentioned, no battles are named, no regiments are identified: not because the subjective particulars are more important than the objective, but because Remarque’s fictional world simply lacks detail.

It was the chapter about the camp of Russian prisoners that affected me the most. They are practically starved, and they pathetically carve wooden figures that they offer in exchange for better rations of food from the Germans. They are so feeble that they no longer masturbate—now, that is a detail you won’t see in many depictions of war. The prisoners sing hymns when any one of them dies, as happens every day. “The prisoners say a chorale, they sing in parts, and it sounds almost as if there were no voices, but an organ far away on the moor.”

With the ugly details—the mention of masturbation, or the description of men suffering from dysentery who sit on poles over the open-pit latrines—one can easily see why the book was banned by the Nazis. In 1933, Joseph Goebbels arranged for copies to be publicly burned. And eventually a dreadful thing happened. Remarque had gone to live in Switzerland, and then to the U.S. His sister, Elfriede Scholz, still in Germany, was arrested for “undermining morale.” After a farce of a trial, she was beheaded—and the costs of her imprisonment and execution were billed to her family. The president of the court said to her, “Your brother is unfortunately beyond our reach, but you will not escape us.”

With these outrageous circumstances surrounding the book, one must acknowledge the courage of the author in daring to express an unpopular viewpoint. Yet there is a reason why All Quiet is so commonly assigned to students in high school. The language is simple, the message is obvious—the author explains it to us many times. And the ironies within the plot creak loudly on their hinges.

My father was a big fan of this novel (not a big surprise if you remember a previous discussion about his obsessions), and also the 1930 movie. I’ve not read it myself, but from the passages you include make me want to give it a read.

You might find this amusing: Growing up, my mother and father would reference the novel’s title during moments in our lives when nobody had much to say or when things suddenly got very still and uneventful. I come from an strange family. : )

I have heard other people use that phrase in a similar way. As time goes on, though, people won’t even know what “Western Front” refers to, and the expression will probably drop out of currency.

I found a tattered paperback once by Remarque. It was set in World War II on the eastern front. While his sister was beheaded in 1943 in Germany, Erich was cultivating a taste in famous actresses, so guess that one was less from personal experience. Cold, the killers and the killed, survival, from the platoon level. Worth reading I thought, but I didn’t rush out and find other books by the same author.

I haven’t read anything else by Remarque, but I am a bit curious about this one that you mention.

I have the original English edition of ‘All Quiet On The Western Front’ in my collection – G P Putnam 1929. The fact that it was reprinted 14 times between March and June that year, totalling 113,000 copies, underscores the popularity; but it was also very much a part of the anti-war literature that began emerging at the time, often penned by former soldiers who certainly had plenty to say but whose literary talents frequently lagged behind. We’re coming up to the centenary of the Western Front now, so I guess it’ll get a bit of profile in the next couple of years – but then, likely, fade again. A pity: we need to remember it. I wrote a book on that campaign, a decade or so ago (it’s available again now… :-)) and recall that even reading the first-hand accounts and diary entries was harrowing enough. Trying to understand and comprehend them as an emotional experience for those who went through it, so I could write about their experiences in a meaningful way, was extremely difficult. But, I thought, also necessary.

Yes, despite my lack of complete enthusiasm about “All Quiet,” I feel that it made a very important statement, and there’s no question that its impact was enormous. That can’t be underestimated. Yet, as you point out, the memories fade again all too quickly. It’s especially true here in the U.S. that we fail to appreciate of the vastness and trauma of WWI. Our part in the conflict was so small, and it happened on the other side of an ocean.