August 1904. General Nogi Maresuke, with the Japanese 3rd Army, besieges Port Arthur. His assault columns make massive rushes against the garrison’s defense lines. The Japanese Naval Brigade brings in two 4.7″ howitzers and pounds the Russian fleet as the ships sit idle in the harbor. Admiral Wilgelm Vitgeft, the uninspiring successor to Makarov, must get his fleet out of harm’s way.

Vitgeft had already made one half-hearted attempt to lead his fleet out of the blockaded harbor and off to the relative safety of Vladivostok. Now all he wanted to do was wait for the Baltic Fleet to arrive. Then Pacific and Baltic squadrons could join forces to defeat Admiral Togo. The only problem: the Baltic fleet had not even departed yet, and it faced a journey of 18,000 miles.

As one commentator observed, “Russia’s primary strategic problems in the Russo-Japanese War were simply Time and Space. Not enough of the former and too much of the latter…. Historically time and space were Russia’s allies…. In 1812 they were Russia’s primary weapons against Napoleon’s Grand Army, and ultimately the keys to her victory. However, in the Russo-Japanese War, Russia found herself transposed into Napoleon’s difficult position.”*

On August 9 a message arrived from the Tsar. Vitgeft must take the fleet to Vladivostok at once! The unhappy man assembled his officers and told them, “Gentlemen, we shall meet in the next world.” One of the men present, a Lieutenant A.P. Steer from the cruiser “Novik,” commented: “When the Commander-in-Chief is in such a frame of mind he imparts it to those around him to a fatal extent. Our squadron started with the firm conviction that it was going to meet with disaster.”# In fact, Steer wrote, Vitgeft even dispatched a telegram to the Tsar upon departure saying that he did not expect to reach Vladivostok.

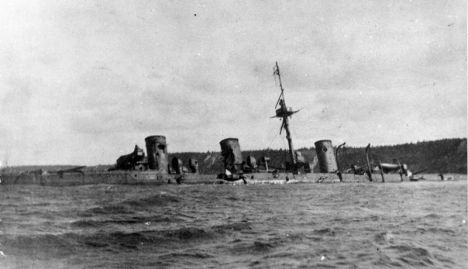

As it turned out, out of the entire Russian squadron of six battleships, four cruisers, and 14 destroyers, only one vessel would make it to the safer Russian port: the “Novik.” And yet not one of the vessels was sunk.

A naval conflict such as the Battle of the Yellow Sea, August 10, 1904, must have been something to see—most of all, of course, the battleships themselves, the largest ships of the fleets. Each of these behemoths took more than five years to build and cost somewhere in the neighborhood of $5 million apiece—in 1904 dollars. They were massive and intricate constructions of gun turrets and funnels, searchlights and lookout stations, armor-plated hulls and the latest gigantic coal-fired boilers. Each had batteries of guns of different caliber and range, typically 12-inch guns with a range of 14km bolstered by a secondary armament of 6-inch guns and arrays of lighter guns designed to deter the torpedo boats that dashed up close for a lethal attack.

But a battleship doesn’t turn on a dime, and neither does it move very quickly. These ships were designed for speeds up to 18 knots, but in practice, mechanical problems, or the necessity of staying in formation, often held them to 14 or 15 knots. Therefore more than three hours passed between the time Japanese lookouts on blockade duty radioed Togo about Vitgeft’s departure and the time the two fleets engaged each other in battle.

Vitgeft caught Togo’s fleet widely dispersed, and he was wise enough to move first to the southwest, disguising his intended destination. So it took Togo a while to form his ships into a battle line. At 1:00 in the afternoon the two lines finally converged, but Togo miscalculated and moved too quickly to “cross the T” of Vitgeft’s line. All at once Vitgeft’s fleet turned to port, and the two fleets were moving in opposite directions, Togo having failed to block Vitgeft’s path. They fired at each other at long range, and Togo ordered each of his ships to turn about quickly. Now the order of his battle line had reversed, with the smaller cruisers in the lead, and they were moving parallel to Vitgeft’s line and pursuing him.

Of all forms of combat, this must surely be the most rigidly limited by laws of momentum and unidirectional movement. But I picture this moment on the Yellow Sea as having its own impressive geometry, as the long, narrow ships turn about and the vectors instantly shift.

At any rate, the Japanese pursuers gradually closed the range, and the guns of the two sides fired off hundreds of shells. There were many hits, and both sides suffered multiple casualties and much damage to their ships. Hours went by, and Vitgeft knew that if he could hold out until dark, he might escape. But at 6:40 in the evening disaster struck for the Russians. A salvo hit the bridge of the flagship “Tsesarevich,” instantly killing Vitgeft and his immediate staff, as well as the steersman. The blast jammed the helm—one account says it was actually jammed by body parts—and the flagship made a port turn so abruptly that the ship heeled over sharply. Crews of the other Russian vessels, not understanding what happened, tried to follow in its wake.

Rear-Admiral Ukhtomsky on the “Peresvet” realized the “Tsesarevich” was out of action and attempted to bring the squadron under control. But his ship’s mast had been damaged by a shell, and he could not hoist his signal flags. Lt. Steer of the “Novik” wrote, “The battleships, which had followed the flagship’s movements, had formed a compact mass around her. They were in no kind of order and heading in every direction…. The Japanese, taking advantage of the general confusion, and especially of the fact that our ships were all clubbed together, increased their rate of fire and poured a hail of projectiles over our distracted ships.”

At that moment, Captain Eduard Shchensnovich of the “Retvizan” bravely turned his ship toward Togo’s battle line, charging into it with guns blazing and drawing relentless fire. This gave the crew of the “Tsesarevich” the breathing space needed to regain control of their vessel. Eventually the Japanese, having expended many of their shells and seeing that the Russians were scattering, turned about to withdraw. But a final salvo severely wounded the heroic Shchensnovich in the stomach. He would survive but never fully recover, finally succumbing to the effects of his wounds in 1910.

Rear-Admiral Ukhtomsky had arranged his signal flags across his bridge indicating an order to return to Port Arthur. It’s not clear how many others were able to see the flags, but five battleships, nine destroyers, and a cruiser headed back with Ukhtomsky to the harbor. For the rest, peculiar improvised decisions were made. The damaged “Tsesarevich” and three destroyers sailed to Kiaochou, where they were interned by authorities in the German-controlled port. Two ships sailed to Shanghai and were interned by the Chinese; one went to Saigon, where the French interned it.

The journey of the “Novik”

Only one of the Russian fleet, the small cruiser “Novik,” made for Vladivostok. They saw Ukhtomsky’s signal flags, but, Steer wrote, “as we had just received positive orders to the contrary from our immediate chief, the admiral commanding the cruisers, we did not follow the battleships. However, I never knew exactly what happened then. I only remember that at nightfall we were steering a very different course from that of the main body.”

For the crew of the “Novik,” a long and difficult journey lay ahead. At first an enemy cruiser pursued them, getting off a shell that killed two and wounded the ship’s doctor. When this pursuer finally fell behind, the worry for the “Novik” became that of fuel. They had to go all the way around the east side of Japan, as the Straits of Tsushima were infested with enemy warships. Knowing they could not reach Vladivostok without stopping somewhere for coal, they sailed north for eight days, doing everything they could to reduce fuel consumption, even throwing scraps of wood and oily rags into the boiler.

Much to their relief, they reached the small port of Korsakov at the southern end of Sakhalin Island. There the crew raced about helping to load up the ship with coal—but there was a problem. On the way in, they had passed a Japanese lighthouse in the Kurile Islands. At first it appeared a dense fog would mask their passage, but it cleared just as they went by, and before long the “Novik” was picking up multiple Japanese messages on its wireless. Soon after departing Korsakov, she came under attack.

The poor little survivor took so many hits that she began flooding from holes in the hull. All but one engine ceased to function, and the steering barely worked. She limped back to Korsakov, sinking fast, and there the crew scuttled her.

They still intended to reach Vladivostok. Now all they had to do was cross 400 miles overland to the port of Alexandroff on the west coast of Sakhalin. After provisioning in Korsakov, the party of eight officers and 270 men marched for weeks through wild taiga where most of the people they met were either hard-bitten settlers, escaped convicts, or Ainu, members of that unique group that belongs ethnographically neither to Russia nor Japan. It was a frontier world of bear-baiting contests, copious consumption of vodka, and a high murder rate. The roads dwindled to mere tracks in the forest, and the “Novik” men found themselves slogging through marshes and sidestepping quicksand that instantly swallowed a coin dropped onto the surface.

After making their way up the Poronay River in small boats by rowing and poling, with many laborious portages, they arrived in Alexandroff on October 14, just as the winter snows began to fall. There a steamer met them to take them across the narrow Strait of Tatary to Nikolayevsk on the Amur. From that point they ascended the Amur via riverboat to Khabarovsk. The last stage of the journey, to Vladivostok, was accomplished on the Trans-Siberian Railway.

Steer wrote, “We arrived [at Vladivostok] on 23rd October, having covered 400 miles across Saghalien [Sakhalin] in forty-five days. This is a record for men so little accustomed to marching as sailors, and moreover we did not leave a single straggler or sick [man] behind. So fine an achievement was no doubt due to that feeling of comradeship and the pulling together which obtained throughout the campaign between officers and men of the ‘Novik.’ But all honor is due to the remarkable impulse given by the two peerless captains under whom we served and who are called von Essen and Schultz.”

Postscript

When the Japanese won the war in 1905, the Treaty of Portsmouth assigned them possession of Sakhalin Island south of the 50th parallel. They raised the “Novik” and rehabilitated her for service in the Imperial Japanese Navy.

Between March 1905 and March 1906 Steer commanded the submarines “Delphin” and “Som” at Vladivostok. Returning to St. Petersburg, he commanded a torpedo boat in Baltic waters for a year, going back to Vladivostok in 1907 to assume command of the destroyer “Skory.” On October 17 that year the crew mutinied, and a petty officer shot Steer dead while he was in bed in his cabin.

The Soviets retook the southern part of Sakhalin in 1945.

—————————–

* Unpublished paper by Major Kenneth Biskner in course on “The Russo-Japanese War,” officer training school. Further source details unknown.

# A.P. Steer, The “Novik” and the Part She Played in the Russo-Japanese War, 1904. London: John Murray, 1912 (published posthumously).

Interesting set of names of the Russian officers, not all of which are Russian names.

I wonder if there was a tradition of Germans becoming officers in the imperial Russian armed forces. Though sometimes of course the German names came from ancestors. For instance, Mannerheim, who you commented about in my Finnish Civil War post, was born in Finland but had a paternal grandfather from Germany. As you know, he served in the Russian army before returning to Finland to lead the Finnish White Army in the civil war, and then played other important roles.

Baron Roman von Ungern-Sternberg, that bizarre and nasty piece of work, comes to mind. Russian nobility descended from Teutonic Knights.

I had to look him up—what a strange and self-defeating character! Certainly a maverick, not part of any historical trend.

My piece on the Bloody Baron can be found here: http://frontierpartisans.com/1246/a-tale-of-the-wild-wild-east/

Thanks—that was interesting. Unfortunately there are certain personality types who find this sort of figure to be heroic.

“no man left behind” is impressive — this was one of Andrew Jackson’s claims in his ordered retreat from Natchez early in the War of 1812. Men who could not walk rode the officer’s horses. He had rather better luck .. his men did not end up shooting him, rather helped him eventually to the Presidency.

Warfare is a fascinating subject. Despite the dubious morality of using violence to achieve personal or political aims. It remains that conflict has been used to do just that throughout recorded history.

Your article is very well done, a good read.