This is one of a series about memoirs, novels, and poems authored by combatants of the First World War. All page numbers shown below refer to Hans Carossa, A Roumanian Diary, New York: Alfred Knopf, 1930.

Hans Carossa’s Roumanian Diary is a somber yet lyrical account by a medical officer with the German army. He was also a published poet, an explorer of deep levels of interior life. The book sometimes frustrated me as I sought external points of orientation. Yet it transported me to a place magically remote that called to mind old-fashioned tales for children, the kind that would have woodblock illustrations of a woodcutter in the forest, a hunchbacked peasant, or a little hut with a puffing chimney beside a stream.

It begins October 4, 1916 in France and ends December 15, 1916 in the mountains of Transylvania. The edition I have, a handsomely printed hardbound, contains no preface. There is nothing to explain why these three months were chosen out of what must have been a longer journal—Carossa noted his perpetual need to leave words behind him as a trail of breadcrumbs. And no background is given about his personal circumstances or about the historical situation of the Romanian campaign of the First World War.

So as I began reading, I felt as though I’d walked into a movie half an hour after it started. I puzzled through the references to “Vally” and “Wilhelm,” finally determining they were Carossa’s wife and son. Adding to the mystery, he often writes about his dreams, so we drift between the real and the unreal. It didn’t help that I knew next to nothing about the Romanian campaign. I consulted history sources and looked at maps. Carossa mentions many place-names. I could find only one or two of them on any maps. This is either because these villages are too small to appear or because the army of Germany, as Austria-Hungary’s ally, used maps with Hungarian versions of place-names since replaced by Romanian.* That is related to the central reason for Romania’s participation in the war: its determination to wrest Transylvania from its place in the Austro-Hungarian Empire. Transylvania was populated mainly by ethnic Romanians.

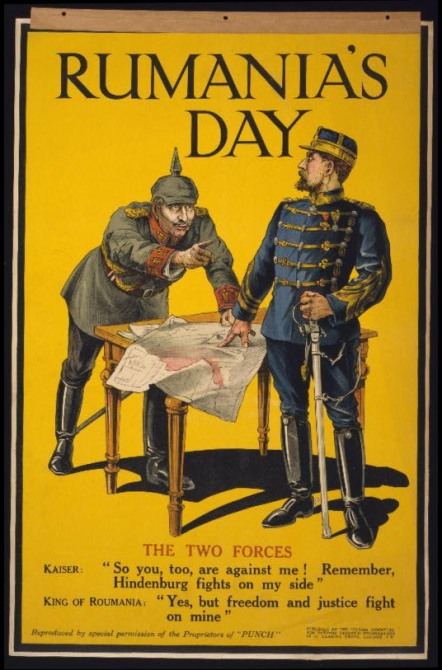

Romania didn’t enter the war until 1916, and it might have fought on either side. When the war started, King Carol I of Hohenzollern wanted to participate as an ally of Austria-Hungary, while the Romanian populace mostly favored an alliance with the Triple Entente.

King Carol died and was succeeded October 1914 by King Ferdinand I, who was married to the Princess Marie of Edinburgh. With her influence added to diplomatic persuasion from Britain, Romania signed a pact with the Allies August 17, 1916, and declared war on Austria-Hungary August 27. In accordance with the cascading effect of WWI alliances, Germany declared war on Romania the next day, and that was swiftly followed by parallel declarations of war by Bulgaria and the Ottoman Empire. Russia became Romania’s most important ally, providing troops of many origins: Carossa mentions Ukrainians and Kirghiz. Bosnian troops assisted on the Central Powers side.

As Roumanian Diary opens, Carossa is at the Somme with the 19th regiment of the Bavarian Infantry Reserve (as I learned from other sources). A 36-year old physician, he serves as medical officer of his battalion.

The Allies had assumed that Germany would be too involved at the Somme and with the Brusilov Offensive in the Ukraine to send troops to Romania. But after Romania attacked Austro-Hungarian troops in Transylvania, Germany sent in eight divisions and an Alpine Corps under the command of General Erich von Falkenhayn. Bavarian divisions were included because they were considered suitable for mountain warfare.

At the Somme, Carossa receives orders indicating that a transfer is imminent, but the destination is kept secret. The order for innoculations against cholera tips him off that they will shift to the Eastern Front. Soon a rumor circulates that it will be Romania. On roads clogged with troops, they march to Aubigny-sur-Bac, east of Arras, and board a train.

I would have thought that a transfer from Western to Eastern Front would occasion ruminations about contrasts in combat environments, or at least about the immediate escape from the nightmare of trench warfare. But Carossa doesn’t write about that, and he didn’t add anything along those lines when the diary was prepared for publication in the 1920s. He focuses throughout on small daily incidents and personal acquaintances.

One of those acquaintances is a man in his battalion identified only as “Glavina.” We learn that Carossa shares the duty of censoring outgoing letters and has become familiar with Glavina’s thoughts through what he writes home. As the battalion prepares to leave France, Carossa writes in his diary, “No letter can be passed which gives any hint of our coming departure. Almost involuntarily I looked for the bold, clear writing of young Glavina, who often writes such wonderful letters to his friends.” (6)

It gradually becomes clear that Carossa forms a deep attachment to this young man, whom he sees as a kindred spirit, a fellow inquirer into the deeper truths of life. And yet, strangely enough, it is not an actual friendship. Later on, in Romania, Carossa writes, “To-day I could not get Glavina out of my mind; he must be breathing at the bottom of that misty sea [the fog-shrouded valley where they are camped] where the moon penetrates only as a pale silvery radiance. I would like to read one of his sentences again, or to speak with him; but he is inaccessibly shy, and his letters no longer pass through my hands.” (70) Carossa remains a silent admirer, finding something consoling in the very existence of this idealistic young soldier, a brightness that sustains him amidst the ugliness of war.

As I see it, his acquaintance with Glavina, and the latter’s eventual death, form the actual framework of Roumanian Diary. This explains why the published diary cuts off abruptly at a date long before Carossa’s service actually ended.

The Bavarian troops trundle eastward by rail through Germany, Austria, and Hungary, bypassing the cafes and the sights of Budapest, much to the troops’ disappointment. They enter Transylvania at Arad, one of the few recognizable place-names in Carossa’s account. As they continue east, they encounter refugees fleeing the conflict. Three children had found a live hand-grenade and accidentally touched it off, wounding themselves and killing their mother. They are carried in stretchers, trailed by their wailing grandmother. By chance, at that moment, “The sun had all at once cleared the mists, and lit up a high mountain which struck us all with amazement. Its lower slopes were of a bleached green intersected by rocks, then came a narrow girdle of fir trees, which looked as if it had been carefully fitted round, and above that soared a mighty peak of glittering snow… dare I admit that in a second the heart-rending sight of the three wounded children was blotted out?” (26)

In the remote villages of the Transylvanian mountains, the houses are all painted the same shade of blue, with steeply pitched roofs “notched unequally like saws.” (31) The soldiers settle near a village where “people returning from Sunday Mass with enormous prayer-books under their arms came flocking from all sides, the men hesitatingly, the women with an airy and confident step. The latter… suddenly darted into their houses and brought back baskets of fruit and pitchers of milk.” (32) The village men start bartering for tobacco, and “one soldier got a dozen eggs for three cigarettes, and another a fat goose for two packets of pipe tobacco.” (33) To the tune of folksongs played by the regimental band, soldiers and girls dance together on the village green.

But now they approach the furthest extent of hostilities, and they see harsh results of the conflict. An elderly woman, naked to the waist and evidently insane, hurls clods of dirt at them—apparently men in her family, serving as frontier guards, were killed by Romanian troops, and she makes no distinctions between sides in her howling at the world. A bit further on they encounter a wounded Romanian soldier, his face swaddled in bloodsoaked bandages. Carossa stops to give him a fresh bandage, observing that fellow members of his unit cruelly laugh at the man.

By the time Carossa and his comrades arrived at their destination in late October, much had already transpired. The fighting had started immediately upon Romania’s declaration of war with its offensive against Austro-Hungarian border units. Germany swiftly moved in with a counterattack starting September 18, clashing with Romanians at Sibiu and pushing them south to the spine of the Fagaras Mountains. There they battled at the Turnu Rosu (Red Tower) and Vulcan passes. Fighting continued there until late November, when the Romanians were forced into the plains south toward Bucharest. One noteworthy figure present at Vulcan Pass was Lieutenant Erwin Rommel of the Wuerttenberg Mountain Corps, the future field marshal.

Carossa’s battalion fought in the Csik Mountains, further east. You won’t find the name of those mountains anywhere in his book. But it’s possible to deduce from two or three references that they fought at the headwaters of the Maros (Mures) River, near Gymes Pass. They had followed the long course of the Maros from Arad as it winds across Transylvania. Of course, Carossa doesn’t speak of regions or campaigns but prefers to talk about individual mountains and individual soldiers.

Carossa’s mountains offer scenes of beauty, though their scree slopes and forests are filled with corpses. “The mountain we climbed was a mountain of blindness and death…. Like a swarm of hornets the shells dashed against the rocks, tearing the flesh from the limbs of the living and dead.” (90)

His entries for November 25-28 describe a different kind of cruelty. A 15-year-old boy acting as an attendant to the unit is instructed to destroy a motherless litter of kittens in a house where the soldiers are resting behind the lines. He takes them one by one and hurls them against the wall of a shed, then returns to the kitchen whistling a tune, unconcerned. One of the kittens survives, gets up, and totters forward with blood dripping from its chin, eventually arriving at the table where its would-be murderer is eating. The boy sees it and offers it food, suddenly overcome by remorse. Over the next days, a growing circle of people attend to it, now all intent that it should survive. It alternately nibbles at its food and tries to wash itself or to nap, growling softly in its sleep. They give it the name of “Matchka.” Carossa places it next to his feet and watches over it, observing a unique dignity in this insignificant animal. But it dies, and the boy who had earlier tried to kill it kneels beside the small corpse and weeps.

Late one day of fierce battle, Carossa walks the stony side of a mountain, attending to the wounded. He finds Glavina, leaning against a granite block: “He was still breathing, but on his face already was the prescient look of the dead…. Fighting down our sorrow and apprehension, we searched for the wound and found at last a tiny splinter driven into the nape of the neck. Soon his breathing ceased.” Carossa finds next to Glavina “a few closely written sheets of paper, which must have fallen out of his pocket.” (91)

Whenever he has a spare moment, Carossa studies these writings. Glavina had composed a poetic text, a call for the survival of spirit in the face of death. One afternoon as the battalion stops for rest in a village, Carossa sits and quietly murmurs the text to himself as if memorizing a sacred text. Noticing that others are listening, he explains that it was found on the dead soldier Glavina, and reads it from its beginning in a clear voice. Its first line goes: “Let us build up a cairn on the mountain of Kishavas, a trophy to the slain on its icebound floor of rocks and juniper!”

The others listen silently. Continuing for 23 short passages of despair and renewal, it says among its concluding lines: “Faith garnered like star-seed, shall glow with a steadfast light. After moons and years it may strike perchance on the clear crystal of the frozen soul, which remains ice, nor will ever melt, but like a curved glass unwittingly may bend the many-colored rays on to a far-off point, where new flame will start from the ancient earth.” (172)

In an inexplicable fit, one of the soldiers abruptly leaves the room and runs toward a building destroyed by Russian shellfire just hours before. He is struck and killed by a shell fragment. As darkness falls, they bury him and fashion a cross with the soldier’s name and the date. Then they continue on their journey, through falling snow. And there the book ends.

*This seems evident from the frequency of “sz” combinations in Carossa’s place names: “Szentlelek” or “Szekely-Udvarhely,” for example. I see the “sz” combinations in Hungarian words and not in Romanian. The two languages belong to different linguistic families. I should also note that in the Csik Mountains, there is a large minority Hungarian population. Yet I cannot find Carossa’s place names even in that area.

Very interesting.

Even today, Romania remains a country that’s hard to grasp. With fluid borders, and seemingly shifting loyalties, it’s role in World War One and World War Two are difficult to fully understand, at least in a cultural context. Like Russia, it’s an enigma, but only more so.

I was glad to have an excuse to read about Romania’s participation in WWI. For understandable reasons, Americans are much more focused on the Western Front, and our limited knowledge of the Eastern Front does not extend to places like Romania. The realms of Central Europe and the Balkans seem alien and unfamiliar—except that, as I tried to express in an early paragraph of this blog, there is some deep association for me that goes back to childhood. I have never been to Romania, but I have been to what are now Serbia and Croatia (in the 70s, when it was Yugoslavia), and to the Czech Republic in the early 90s shortly after the collapse of the Soviet Bloc. In those places, I again felt a strange sense of recognition. It’s not anything that is easy to articulate. When I was in Prague watching puppeteers on the bridge and looking up to the fantastic castle on the hill (thank goodness Prague escaped destruction in the world wars), I felt a connection with the culture there. It may go back to my reading of Anthony Hope’s Ruritania books (Prisoner of Zenda, etc.)!

In terms of an odd book recommendation, let me recommend “A Life In Secrets” about Vera Atkins. Atkins was a significant figure in one of the British clandestine services during World War Two and had grown up in what was then part of Romania (and now part of Hungary, in a family of Jewish extraction. Very interesting look at a very mysterious personality and a lost world.

As a really minor followup, it’s really interesting to see how this era, i.e., the World War One era and the proceeding years, really lives on with Romania in some fashions.

The proper borders of Romania and its neighbors were disputed during the Great War. Following the Great War, they remained in dispute and both Hungary and the Soviet Union weren’t happy with Romanian borders. Romania foolishly threw in with the Germans during World War Two, but even at that Hungary and Romania remained so hostile to each other that their forces in the East couldn’t be posted next to each other, as they’d fight each other instead of the Red Army.

Romania switched sides to the Allies at the 11th hour (as if that was going to help them) and following World War Two, its borders were adjusted again. Today, the country of Moldava borders it, but the cultural distinction between Moldava and Romania is non existent, so even now, with the forced movement of peoples following World War Two, Romania has a bordering region, indeed an entire country bordering it, that would sort of seem to properly be in Romania, but isn’t going to be.

Thank you for this short, clear description of later events. So much history! So much to learn! This is why, as I grow older, I have turned more and more to the subject of history and its endless, enormous fascination. I feel very humble in the face of this subject—but isn’t it great in our lives to have a sense of something interesting and inexhaustible?

Indeed, it is great!

Romania is one of those strange regions of the glove that’s always with us, and seeming never with us, always in the past, but part of the present. Even the language is strange, being a Latin derivative, stranded there in the east. Part of the Roman Empire reaching out to us, but part of the Byzantine world more so. . .

P.S. As long as Romania still has the important Black Sea port of Constanta, Moldova may not have too much strategic importance, at least as far as shipping is concerned.

I’m thinking it is likely of no strategic importance, but Romanian history seems to be full of spats over areas of low importance. Population only, really.

Very interesting land, with some really tragic and terrible history really. The World War Two history of the country is really peculiar, and features some of the worst early atrocities against the Jewish population of any region.

A superficial glance at a WWII history shows me that Romania was neither fish nor fowl (not obviously belonging on either side of the fight), but essentially a plaything in the hands of larger powers, with its Ploesti oilfields probably the main thing that created an interest. I see that it changed allegiance partway through. I also see that the same issue of Hungarian and German interest in Transylvania continued from one war to the next. Regarding the Jewish issue, I will read further about that. Thanks for your input.

I’ll expound a bit on that, although I don’t want to be hijacking your very interesting thread here, so I’ll stop thereafter so as not to do so.

Romania’s royal government fell at the beginning of World War Two as a fascist movement, the Iron Guards, gained strength. While its politics hadn’t reached the state of a western European nation between the wars, I think the evolution towards a fascist state were not anticipated widely until the Iron Guards gained strength right at the start of the World War Two. Of course, it was at time when fascism was on the rise and seemed by many as a rising force, and fascist movements or fascist like movements existed all over the continent at the time.

When the royal government fell, and the fascists took over, the country became a military dictatorship which threw in against the Soviet Union. I’ve never looked at its motivation for doing that, but what does seem clear is that the Romanian military government willingly joined in with Germany rather than being forced. It must have appeared to them at the time that a German victory was inevitable and they wanted to be on the winning side. They may have seen an immediate territorial gain by doing so, and they may have seen a political advantage to being associated with what they assumed would be the winning side. And also, the military government of Romania was strongly anti communist and would have likely have viewed the German war against the USSR as being one that it had to be in. Certainly from the flip-side, it would have been difficult to imagine a Soviet victory in the East being one that would not have overrun Romania in some fashion anyhow, and they may have been cognizant of that.

One aspect of Romania at that time is that its rural populace remained virtually in an earlier era, compared to European nations to the west. That’s sort of touched on a bit in some of the photographs you have linked in above in a way. Most Romanians in 1940 were peasants and their life differed little from that depicted above, which for that matter could have been set a century earlier. Even now, Romania is a bit backward compared to many other European nations. Anyhow, when the Iron Guard took over Romania and the nation lurched towards Germany, there was some really horrific violence in the country directed against its Jewish population. While likely inspired by the German example, it wasn’t German directed, and was sort of spasmodic. It seems to have been a release of a little known and little appreciated retained Antisemitism amongst the rural population which may have been both unknown due to, and caused by, their fairly low level of education.

The Romanian army itself fared very poorly in World War Two in large part because it wasn’t a modern army compared to other combatants. It would be easy to say that it remained like its army of World War One, but that same statement could be made about other armies that fought in WWII. It was basically equipped like a World War One vintage army, but with a structure between its enlisted men and officers that was reminiscent of the Napoleonic era. Its officers treated its enlisted men poorly, and when they were lead by German officers they actually did quite a bit better.

To wrap up, the military dictatorship fell as the Soviets advanced and various forces in Romania sought to return the army to the country for its own defense. In the end it fell and the new government brokered a peace which required it to switch sides, one of at least three or four examples of that occurring during the war. By the time it did that, however, the game was really up and there was no salvaging the situation, although it did lead to some fierce fighting between Romania and Hungary.

Thank you!