I would like to introduce you to Lt. Tadayoshi Sakurai of the Imperial Japanese Army.* Having landed on the Liaodong Peninsula with General Oku Yasukata’s 2nd Army, Sakurai’s unit arrived just barely too late for a hard-won Japanese victory at Nanshan, May 26, 1904. This victory opened the way for the Japanese to advance overland to Port Arthur.

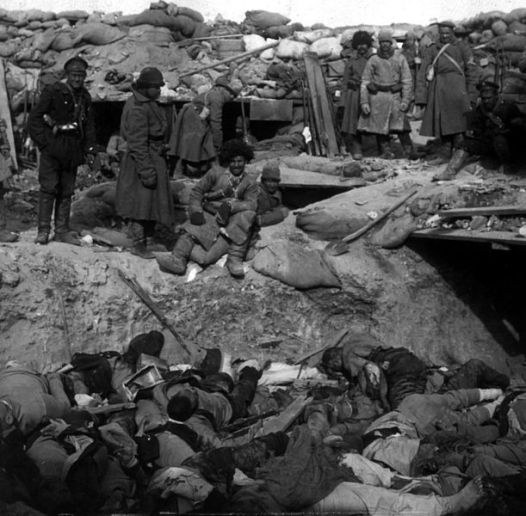

Smoke still hung over the battlefield when he and his comrades walked the ground, and the idealistic 25-year-old saw for the first time the horrors of battle. “It is shocking to see dead bodies piled up in this valley or near that rock, dyed with purple blood, their faces blue, their eyelids swollen, their hair clotted with blood and dust, their white teeth biting their lips…. Everywhere were scattered blood-covered gaiters, pieces of uniform and underwear, caps, and so on; everywhere were loathsome smells and ghastly sights.”#

Little did Sakurai know that he would go into the heart of that hellish world after his division was transferred from Oku’s army to bolster General Nogi Maresuke’s 3rd Army in its attack on Port Arthur.

Sakurai’s memoir, Human Bullets, was published shortly after the war and came out in an English translation in 1907. It’s available now in print and electronic editions, and somewhere on the Web I stumbled across a negative review by a contemporary reader: “I really wanted this book to be good, but it was just such a damn bore that the memory of struggling through it overshadows any positive thing I could say.”

I didn’t find it boring at all, and yet I understood the response. If you compare Human Bullets with memoirs of the past few decades by soldiers of the western world, especially truly great accounts like Philip Caputo’s memoir of Vietnam, A Rumor of War, you’ll find the states of mind so different that the authors might as well be from different planets. The trouble is, Sakurai’s cherished ideas of loyalty to the Emperor and joy in self-sacrifice have sort of a tinny sound to modern ears.

If he’d possessed current attitudes about combat, Sakurai would likely have felt bitter about his experience. His commander, General Nogi, threw away the lives of thousands of men. A veteran of Japan’s war against China in 1894-95, he had seen the Chinese surrender Port Arthur after just one day of fighting, at a cost to the Japanese of just 16 casualties.

This time it would not be so easy. Under the Russians, Port Arthur was defended by barbed-wire entanglements, electric fences, searchlights, trenches, and machine guns. The technology of war had developed nearly to the stage of WWI, and the Japanese knew no way to deal with these defenses other than to throw countless men at them. The high value placed on willingness to die in combat—the concept of suicide for a cause as noble—only exacerbated the problem.

It would take five months and 60,000 Japanese casualties (about half that number for the Russians) before the garrison would surrender. Nogi kept sending his assault columns against the fortified hilltops that surrounded the town—the men literally climbed over the corpses of their comrades as they scaled these rocky little prominences under hailstorms of machine-gun fire.

Nogi spent weeks focusing on points east of the town, failing to recognize the strategic importance of a point to the west overlooking the harbor, the famous 203-Meter Hill. Field Marshal Oyama’s chief of staff, General Kodama Gentaro, who’d been occupied with planning the Manchurian campaign, had to point it out to Nogi when he visited Port Arthur.

Lt. Sakurai’s account is full of references to old war songs, myths, religious traditions, and expressions of patriotism. He said, “We soldiers were always ready to ‘jump into water and fire at the Great Sire’s word of command’,” quoting a famous war song. He spoke of Yamamoto-damashii, a reference to a province captured by an early emperor that came to symbolize all of Japan and its spirit. Where the soldiers went, “the heavens will open and the earth crumble”—another line from a war song. A hawk was always a symbol of victory; the Kim ga yo, the national hymn, was sung at moments of triumph; and “Banzai” (literally “ten thousand years”) would be shouted in the emperor’s name.

The sense of belonging to powerful and long tradition fortified Lt. Sakurai as he lived through experiences that otherwise could have been unendurable.

His regiment first went into action June 26 at Waitu-shan and Kenzan, fortified hills on Port Arthur’s outer defense lines. The Japanese took these points and dealt with counterattacks from the Russians. But it was during the first general assault on Port Arthur, starting August 19, that the huge numbers of casualties began to roll in.

During a lull in the fighting, Sakurai encountered another lieutenant by the name of Yoshida, an old friend from his own province. He asked Yoshida what he was doing wandering about in the field of combat. “Please look at these corpses!” came the answer. Sakurai wrote, “There were dark shadows about him which I had thought were the recruits of our regiment. I could not help being astonished when I found that those heaps of khaki-colored men were the dead or wounded soldiers of Lieutenant Yoshida’s command. What a horrible sight! Their bodies were piled up two or three or even four deep; some had died with their hands on the enemy’s battery, some had successfully gone beyond the battery and were killed grasping the gun-carriages. A sad groaning came from the wounded who were buried under the dead. When this gallant assaulting column had pressed upon the enemy’s forts, stepping over their comrades’ bodies, the terrible and skillful fire of the machine guns had killed them all, close by the forts, piling the dead upon the wounded.”

Sakurai was soon to be wounded himself with multiple injuries. His right arm was shattered, and he nearly died from loss of blood. The brave assistance of a stranger enabled him to be carried from the battlefield for medical attention. He would no longer be capable of participating in the fight.

One frontal assault followed another. After weeks of desperate struggle, the Japanese captured the critically important 203-Meter Hill on December 5. From this vantage point, General Nogi was able to bombard the remains of the Russian fleet anchored in the harbor. Over the same period, the Japanese tunneled under Russian fortifications and destroyed them by exploding mines.

On January 1, 1905, without discussing the matter with his fellow officers, General Anatoly Stoessel surrendered to the Japanese. Parties on both sides were surprised, especially considering that Port Arthur still had ample stores of food and ammunition. Stoessel and two other officers, Foch and Smirnov, were eventually court-martialed.

The remains of Nogi’s army proceeded northward into Manchuria to join the other Japanese armies at the Battle of Mukden.

* Generally in my blog I have followed the Japanese convention of giving the family name first. However, since Lt. Sakurai’s book has been published in English with the family name second, I have followed the publisher’s example to avoid confusion.

#All quotes are from Tadayoshi Sakurai, Human Bullets: A Soldier’s Story of the Russo-Japanese War. University of Nebraska Press: Lincoln and London, 1999.

quite a contrast to the battle at Yalu River (or the previous taking of Port Arthur from the

Chinese) which were so easy for the Japanese. The general beaten after a 7 month siege court martialed, but not the one who managed to lose in a day ?

“I didn’t find it boring at all, and yet I understood the response. If you compare Human Bullets with memoirs of the past few decades by soldiers of the western world, especially truly great accounts like Philip Caputo’s memoir of Vietnam, A Rumor of War, you’ll find the states of mind so different that the authors might as well be from different planets. The trouble is, Sakurai’s cherished ideas of loyalty to the Emperor and joy in self-sacrifice have sort of a tinny sound to modern ears.”

Fascinating observation. Indeed, looking into what that reveals might be an interesting, or perhaps frightening, endeavor.

Not to get too pompous or philosophical about it, but the difference in attitudes might be summarized (a bit simplistically) as one between belief in structures of objective meaning or value versus a more relativistic, disillusioned stance. I find much to admire in the traditional attitudes, and at the same time I can’t pretend to ignore modern insights.

There was a lot of conflict, maneuvering, and incompetence among the top Russian officers during the Port Arthur siege, and the process by which the surrender was decided on doesn’t look good upon close scrutiny. I don’t know much about the 1894 battle at Port Arthur, but the Chinese viceroy was in fact demoted or stripped of his title after the quick defeat.