This is one of a series about memoirs, novels, and poems authored by combatants of the First World War. All page numbers below refer to Siegfried Sassoon, Memoirs of an Infantry Officer. New York: Penguin Classics, 2013.

Embedded within the pages of Memoirs of an Infantry Officer, you will find an account of a British second lieutenant on the Western Front, complete with vivid scenes of the Somme and Arras. But the book’s unique value concerns events off the battlefield, a personal and solitary journey undertaken by Sassoon.

Infantry Officer is the second volume of Sassoon’s trilogy, The Memoirs of George Sherston, a fictionalized autobiography. Names have been changed, events rearranged. The crux of the book is a description of Sherston’s growing disgust with the conflict and his decision in 1917 to make a public protest against “the War.” These episodes run pretty close to Sassoon’s real experience, and they tell how Sherston/Sassoon was eventually packed off to a mental hospital. The top brass were embarrassed by this protest on the part of a decorated officer, but they feared making a martyr of him. Rather than sending him to prison, they decreed that he suffered from shell shock, and he was quietly removed from public view.

Sassoon endowed the character of Sherston with the hearty sportsman side of his own past (fox-hunting, cricket) but omitted the writing of poetry (Sassoon was a successful poet at the time the war started). Sherston does happen to read quite a lot. At one point during the Somme campaign: “Late that night I was lying in the tent with The Return of the Native on my knee. The others were asleep, but my candle still guttered on the shell-box at my elbow… I felt very wide awake. How were things going at Bazentin, I wondered? And should I be sent for tomorrow? A sort of numb funkiness invaded me. I didn’t want to die—not before I’d finished reading The Return of the Native anyhow.” (79)

The reader of course understands this is a bit of amiable self-mockery, not an insane devotion to Thomas Hardy. The greatest pleasure of reading Infantry Officer is getting to know a character you’d like to have for a friend. He’s brave but willing to admit self-doubt, amused at times by the wartime world but sensitive to its horrors. He can entertain with a bit of devastating social insight, as when he describes a “large dining-room… full of London Clubmen dressed as Colonels, Majors, and Captains with a conscientious objection to physical comfort.” But his take on this sort of thing is never bitter. He goes on to say: “But, after all, somebody had to be at the Base; warfare offered a niche for everyone, and many of them looked better qualified for a card-table than a military campaign.” (135)

An episode at Mametz Wood shows Sherston in his best brave-yet-foolhardy combination. Two companies make a midnight attack on a German position below the Wood. As the battle sputters along, there is considerable confusion on poorly reconnoitered terrain. Sherston is first ordered to take his bombers forward, but shortly thereafter told to bring them back (bombers meaning soldiers carrying Mills bombs). He sends them toward the rear but continues forward himself without really knowing why. A man named Kendle of his company loyally stays with him, and they wander across shell-pitted ground in the pre-dawn hours. They stop for a short rest, and Kendle falls asleep with his head on Sherston’s shoulder before they struggle to their feet once again.

Along the way, the pair encounter all varieties of human response to the terrors of combat. An unhinged officer runs toward Headquarters in the rear, babbling of not being able to “find the Germans” until Sherston takes out his pistol and threatens to shoot him unless he returns to his position. Sherston knows that if the man reaches HQ in that condition, he will end up court-martialed for cowardice. He and Kendle stagger on until they reach a recently captured trench. Three apathetic officers sit listlessly on the firestep, in striking contrast to an energetic NCO named Fernby who briskly discusses the situation with Sherston. They agree the trench must be dug deeper immediately, as the men are exposed to enfilading fire and the sun will soon rise.

The ever-unfolding contrasts between courage and cowardice fill Sherston with incoherent but intense emotion. They come under fire from a sniper, making out a helmet bobbing up across the valley. Kendle crawls out from behind the bank to fire back, gets off a shot, smiles back at Sherston and Fernby, and is felled by a bullet to the forehead as he turns to fire again.

Burning with rage, Sherston races alone across the valley to “settle that sniper.” Panting with exertion as he climbs the opposite slope, he throws a couple of bombs and reaches the enemy position. “Quite unexpectedly, I found myself looking down into a well-conducted trench with a great many Germans in it. Fortunately for me, they were already retreating. It had not occurred to them that they were being attacked by a single fool; and Fernby… had covered my advance by traversing the top of the trench with his Lewis-gun.”

He sits down in the trench, wondering what to do next, now that he has “occupied” it. Realizing the Germans might return any moment, he calms his thoughts by counting sets of equipment left behind by the fleeing soldiers. “There were between forty and fifty packs, tidily arranged in a row—a fact I often mentioned (quite casually) when describing my exploit afterwards.” (67)

Eventually, knowing he can do nothing more, he runs back to his trench. He stays in the combat zone all morning, ignoring an order to report to HQ, finally returning that afternoon to face the blithering rage of his colonel. His little excursion, it turns out, had forced a delay in a planned artillery bombardment while they waited for “Sherston’s patrol” to come back. So his actions were, in a sense, counterproductive. But how many of his comrades must have felt much-needed encouragement when they learned of the deed?

More and more, as the Somme campaign drags on, Sherston struggles with a sense of helplessness in the face of interminable war. One evening he takes a stroll, watching the pale orange beams of the sun streaming down on a fading, melancholy landscape. “For me that evening expressed the indeterminate tragedy which was moving, with agony on agony, toward the autumn.” (82) As a solitary observer, he can do nothing to stop the war, he feels, but only observe an Armageddon that surpasses understanding.

At the end of the summer he is invalided out with a severe case of enteritis. Given his praiseworthy record—he has by now earned a Military Cross—he is allowed a generous leave back in England. Once there, he finds himself matching the attitudes of civilians back home against the actualities of war. At the hospital he observes a father-son pair who embody this disjunction. The solicitous father comes every day to wheel his sullen son across the lawn. The son has lost a leg, and often glares at his father. But the father is proud of his boy. “I heard him telling one of the nurses how splendidly the boy had done in the Gommecourt attack, showing her a letter, too, probably from the boy’s colonel. I wondered whether he had ever allowed himself to find out that the Gommecourt show had been nothing but a massacre of good troops.” (95)

Once released from the hospital, he stays with his Aunt Evelyn at her estate in the Weald, a famous area of woodlands and fields in the southeastern counties of England. He wanders about the grounds, noticing signs of wartime decay: the neglected stables, the overgrown garden. England has progressed from patriotic enthusiasm to fatigue and deprivation—but still, the vast majority of citizens express support for the war.

In late November Sherston is cleared by the medical board and reports to his regiment’s home camp, near Liverpool. For weeks he endures a tedious existence, relieved by the arrival of his friend David Cromlech (a fictional name for Robert Graves). They have contentious literary discussions, Cromlech deliberately taking bizarre positions (Homer was actually a woman, Milton was worthless). This extends to music as well (Northern folk-ballad tunes are superior to Beethoven’s Fifth). These assertions are contested by Sherston even while he realizes Cromlech delights in pushing his buttons.

In February Sherston returns to France. He moves steadily back toward the inferno, from the divisional base camp at Rouen to his battalion’s camp at Morlancourt, behind the lines, and finally along a series of dilapidated trenches. He is being drawn inexorably into the Battle of Arras. “Stage by stage, we had marched to the life-denying region which from far away had threatened us with the blink and growl of its bombardments. Now we were groping and stumbling along a deep ditch to the place appointed to us in the zone of inhuman havoc.” (161)

The immediate objective of his battalion is to occupy a portion of the Hindenburg Line, and this is accomplished in a swirling chaos of bombardments and advances past the bodies of earlier casualties. Sherston notes the presence, at this stage of the war, of increasing numbers of ill-trained men in the ranks and a lack of competent NCOs. He finds himself in close quarters with two officers new to the front: an uncouth Welshman and a snobbish Oxford grad. Despite bad table manners and excitable talk, the Welshman will be able to take care of himself, Sherston decides. But he worries that the disapproving Oxonian will become unhinged, and he takes him on a tour of the battlefield during a quiet moment to give him a gentle introduction to the horrors. Both newcomers are killed within a few months.

Sherston is soon wounded himself as he explores along a trench in that sub-battle of Arras known as the Second Battle of the Scarpe. It’s a gift from a sniper: a bullet that neatly drills him through the chest, narrowly missing his jugular and his spine. Soon he is back in England, first in hospital and then, thanks to a little string-pulling, convalescing at “Nutwood Manor,” a Sussex estate.

In his first days at the hospital, Sherston ponders his nation’s involvement in the war. “I cannot claim that my thoughts were clear or consistent. I did, however, become definitely critical and inquiring about the War.” (187) His experience at Nutwood Manor reinforces these critical thoughts. Although the resident lord and lady do everything they can to care for their four convalescing officers, “Lady Asterix” complacently believes they should be happy to have done their duty and will be rewarded in the afterlife. Sherston does his best to suppress rude thoughts of disagreement, but the difference in their attitudes becomes increasingly apparent. Lady Asterix happens to be present when Sherston opens a letter informing him that two good friends in his battalion have been killed. When he blurts out the news, the lady serenely says, “But they are safe and happy now.”

Sherston has four weeks before he is required to report back for duty. Soon he decides he must make a public statement against the war, even if he will be court-martialed for it. But while he has all the necessary determination and courage, the way to proceed is not so obvious. His first thought is to ask the editor of the “Unconservative Weekly” (“The Nation”) to publish his statement. In a meeting with the man, “Markington” (H.W. Massingham), he is suddenly introduced to a world of political analysis quite foreign to him. Markington speaks of Russia’s request for England to clearly state her “War Aims,” and England’s refusal. “And now Markington had gloomily informed me that our Aims were essentially acquisitive, what we were fighting for was the Mesopotamian Oil Wells.” (209)

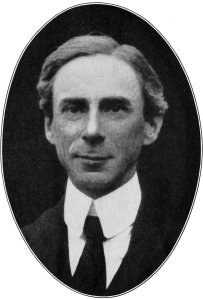

This episode of a soldier/sportsman’s introduction to the realm of global politics ends up being quite humorous. Sherston wants to hit Lloyd George on the nose, and to “stop strangers in the street and ask them whether they realized that we ought to state our War Aims.” (209) Throughout the following period, Sherston is constantly bedeviled by incongruous doubts—not about his purpose, but about the annoying details. He is advised to meet leading pacifist “Thornton Tyrell” (Bertrand Russell). Should he first read the works of that famous philosopher and mathematician? He does eventually obtain one of Tyrell’s works, starts underlining what seem to be the important passages, consults the dictionary, scratches his head, and ends up casting it aside as a hopeless enterprise—the book is too “full of ideas.”

But with Tyrell’s help, he is introduced to a sympathetic M.P. who will read Sherston’s declaration in the House of Commons. He sits down to draft the actual statement. After much agonizing labor, he produces something simple and eloquent. “I am a soldier, convinced that I am acting on behalf of soldiers. I believe that this war, upon which I entered as a war of defence and liberation, has now become a war of aggression and conquest…. I have seen and endured the sufferings of the troops, and I can no longer be a party to prolong these sufferings for ends which I believe to be evil and unjust…”

The M.P. will wait to bring up the matter in Parliament until Sherston has submitted a copy of his statement to his colonel, which he will do only when he is required to report for duty. In the meantime Sherston goes through the motions of military procedure, applying for an instructorship with cadet officers as his chosen duty when his leave will expire. In reality, he believes he will go to prison. It is painful for him to chat with fellow officers while the time bomb of his declaration is set to explode. He has to spend two weeks with his Aunt Evelyn without revealing his seething thoughts. At a train station bookstall he searches for something that will give him consolation and grabs a copy of The Morals of Rousseau, a thinker with whom he has no familiarity. But rather than consolation, he finds only that a nonsense couplet by Cowper goes incessantly through his mind: “I shall not ask Jean Jacques Rousseau/ If birds confabulate or no.” “I mention this couplet because, for the next ten days or so, I couldn’t get it out of my head.” (234)

Oddly enough, it is these details and incongruities that get at the essence of the man. He is brave and determined, but always gently mocking himself. You might even say the self-mockery is a matter of principle.

At last his leave expires and he receives the expected order to report to the Liverpool depot. Now he sends off his statement to the colonel, saying he refuses. The military wheels start to turn. He is interviewed first by an embarrassed major and then by the colonel, who demands to know why he isn’t still interested in “crushing the Prussians.” Sherston returns to his hotel and awaits developments.

He doesn’t want to be rescued from his situation, as he is in it by choice. But his friend Cromlech materializes with important news. It turns out Cromlech has spoken with relevant officials and helped to arrange that his case be treated as a medical one. A “big bug” at the War Office has gotten involved, and they will refuse to court-martial him. For Sherston this is a let-down of sorts, but on the other hand, he has made his statement, and he won’t have to go to prison. Waves of relief wash over him.

As he stands before the medical board, the silly couplet about Rousseau comes into his head again, and he feels tempted to say it out loud. “Probably it would be the best thing I could do, for it would prove conclusively and comfortably that I was a harmless lunatic.” (246) A “kindly neurologist” meets his distracted eye, and before long the matter is decided. He will be treated for shell shock at “Slateford War Hospital” (Craiglockhart).

The volume ends there, and Vol. 3, Sherston’s Progress, describes his time at the hospital, where he meets an admirer, Wilfred Owen. Eventually he returns to the Front.

Great post – and one that got me thinking. Max Hastings has been quite critical of late about what he calls the ‘poets interpretation’ of the First World War – the vision of senseless slaughter, and blaming Sassoon in particular for helping popularise it. In some ways Hastings has a point; there was more to the First World War than that, and demonstrably so. And yet, as your post makes abundantly clear, the ‘poets view’ also had a point; for here was a generation of young men who were traumatised by what happened, and understandably so. Their experience was real, not just for them but also for the many others who suffered similar fates. Putting the two views together gives us a highly dimensional insight into the First World War as a social experience – underscoring the fact that a general interpretation of history often stands at some dissonance with specific individual experience.

I haven’t read Max Hastings—I’ll have to look for what he’s been saying about WWI. But if he characterizes Sassoon as anti-war in some generic sense, as in being a pacifist or objecting to every kind of warfare, that doesn’t seem right. Sassoon volunteered for service right away, believing England was fighting for a good cause. And, as mentioned above, he returned to the Front after his time at the mental hospital. What has happened, though, is that many subsequent writers and thinkers have USED Sassoon, Owen, and others to bolster their own across-the-board anti-war opinions, freely distorting the opinions those men held to make their point. I like your point about the difficulty of melding individual experience into a broader interpretation of the war.

Hastings is a great writer, but I haven’t read his World War One volume yet either. I’m currently reading his book Inferno, which is very good.

Anyhow, at the risk of being very far off the mark, I doubt that Hastings characterizes Sasson fully that way, so much as he might be making the case (with with he isn’t alone) that the sort of gloomy “lions lead by donkeys” view of the war, or the “Oh What A Lovely War” sort of portrayal, isn’t really accurate and doesn’t reflect the views at the time.

Hastings isn’t the first to do that recently, it should be noted. An English volume (I’ve forgotten the author’s name) that came out a few years ago examined the immediate post war views of English veterans and found them to be largely proud of their service in the war, and of they view that it had been a just war and that it had been won. According to that author, the “poet’s view” really came in after World War Two, when the UK sank into despondency over it’s late war/post war decline and accordingly examined World War One. Owens poetry really circulated widely for the first time at that point, not after World War One.

Not that this undercuts your point, however.

One major thinker who endlessly promoted the idea of WWI as meaningless and melancholy, and who focused on Sassoon as an exemplar of this perspective, was Paul Fussell, author of a study of the war focused on the British poets and writers titled “The Great War and Modern Memory.” I find myself strangely irritated by his point of view, so much so that I picked up the Sassoon book with reluctance because my edition had an introduction by Fussell. Fussell’s book won major awards and acclaim. Fussell had an unhappy experience himself in WWII, and that, combined with his strong Anglophile tendencies (he was American), led him to become a kind of cheerleader for the “war is meaningless” perspective, using the likes of Sassoon and Owen to supposedly prove his point. In America this became a highly popular point of view after Vietnam–a totally different kind of war. Pat Barker’s “Regeneration Trilogy” mines the same vein. My first version of this piece on Sassoon had an anti-Fussell tirade in it which I removed. I was interested to learn that eventually there was a counter-reaction to Fussell’s book, saying that he had read very selectively to reinforce the point he wanted to make.

Again, I’ve enjoyed reading this series and your thoughtful analysis on these works, Jenny. Thanks for all the work you put into them.

I’m gad you like the series, Kent. I tremendously enjoy doing these pieces. It’s quite a process. I start by reading the book at least once, dogearing particular pages of interest. Then I write out a draft in a spiral notebook in a certain format that I use for anything I write that’s fairly long and complicated, and I revise several times. Then I select the photos/pictures to go with the piece. Then I look up anything I still have questions about, and finally I type it into my wordpress dashboard. I enjoy every step of this. There’s something about it that perfectly suits me.

I like your “old school” method of writing. Recently I started keeping track of all my hiking adventures in a hard copy journal — haven’t done anything like that for years. I’m finding that my penmanship has really deteriorated, but it’s slowly improving. I’d gotten to the point where any notes or ideas I jotted down were in electronic form — usually on my cell phone.

quite a post .. I’ll put this Sassoon on my list of authors to read ..

On poets, one thing that’s interesting to note in general is that the writing of the time in general was quite poetic. For example, T. E. Lawrence’s war memoir, Seven Pillars of Wisdom (which I hope shows up here) is almost Homeric in its text.

True poets seemed very much more in the common circulation at the time, rather than in literary magazines or in boxed entry in The New Republic. For whatever reason, people just liked poetry more, it seems. I don’t know about other languages, but certainly in English there seems to have been quite a few poets in circulation, in every English speaking country. It was sort of the last golden age of poetry, just as it was sort of the high point in the golden age of poster art.

Excellent point, Pat. Poetry in general was a part of everyday experience for many people. My grandparents memorized verse as a kind of storehouse of good things they could turn to at any moment in their lives.

“Seven Pillars”–to be honest, I’d avoided that because it is such a long, hard read. (I’ve dipped into it before but never read it cover to cover.) I’ll have to think about that. It certainly takes us to a very different sphere of the war.

Seven Pillars is only a hard read for the the first 80 or so pages. After that, you acclimate to the florid text and it becomes natural pretty quickly. At first, however, it’s pretty tough slogging.